Olive Rush’s life

OLIVE RUSH GREW UP ON A QUAKER FAMILY FARM

Olive Rush (Rush Family Photograph Album)

Olive Rush’s grandparents, Iredel Rush and Elizabeth Bogue, were born in North Carolina. They moved in a covered wagon to the newly open state of Indiana just after their 1829 marriage, because they wanted to live and farm in a place without slavery.

Iredel and Elizabeth Rush purchased the land that became Rush Hill, the family farm, in 1831 and 1833. It was “heavy timbered large oak poplar sycamore shugar trees elm.” ¹ Iredel cleared trees, fenced fields, farmed, cared for livestock, built furniture, a cabin, a barn, outbuildings, and a house. Elizabeth gardened, cooked, preserved food, spun linen and wool into cloth, made clothes and bedding. They raised eight children. One son, born in 1836, was Nixon Rush.

Nixon Rush and his wife Louisa Winslow Rush moved into Rush Hill some years after their 1862 marriage. They farmed, purchased the land from his siblings, and shared the house with his widowed mother, her youngest daughter and eventually her second husband. Elizabeth and Louisa each had a kitchen space, and they shared the gardening, food preservation, spinning and weaving work. Nixon and Louisa raised six children. The fourth, born in 1873, was Olive Rush.

Olive Rush’s parents and grandparents were devout Quakers. They helped found two Indiana Meetings – the Back Creek Meeting in 1831 and Fairmount Meeting in 1852. The farm was a well-used stop on the Underground Railroad. Because of Nixon’s Quaker pacifism, he decided not to fight in the Civil War, though he abhorred slavery.

Olive Rush’s birth family used “plain speech” (thee, thou) at home. Her grandparents wore plain clothes, but her parents and their children did not.

Their Quaker Meetings were silent meetings, managed by elder members of the communities. Rush’s sister Myra wrote in her 1943 memoir: “In my childhood we never had a hired minister. There was always ‘waiting for the spirit to move.’ “ ²

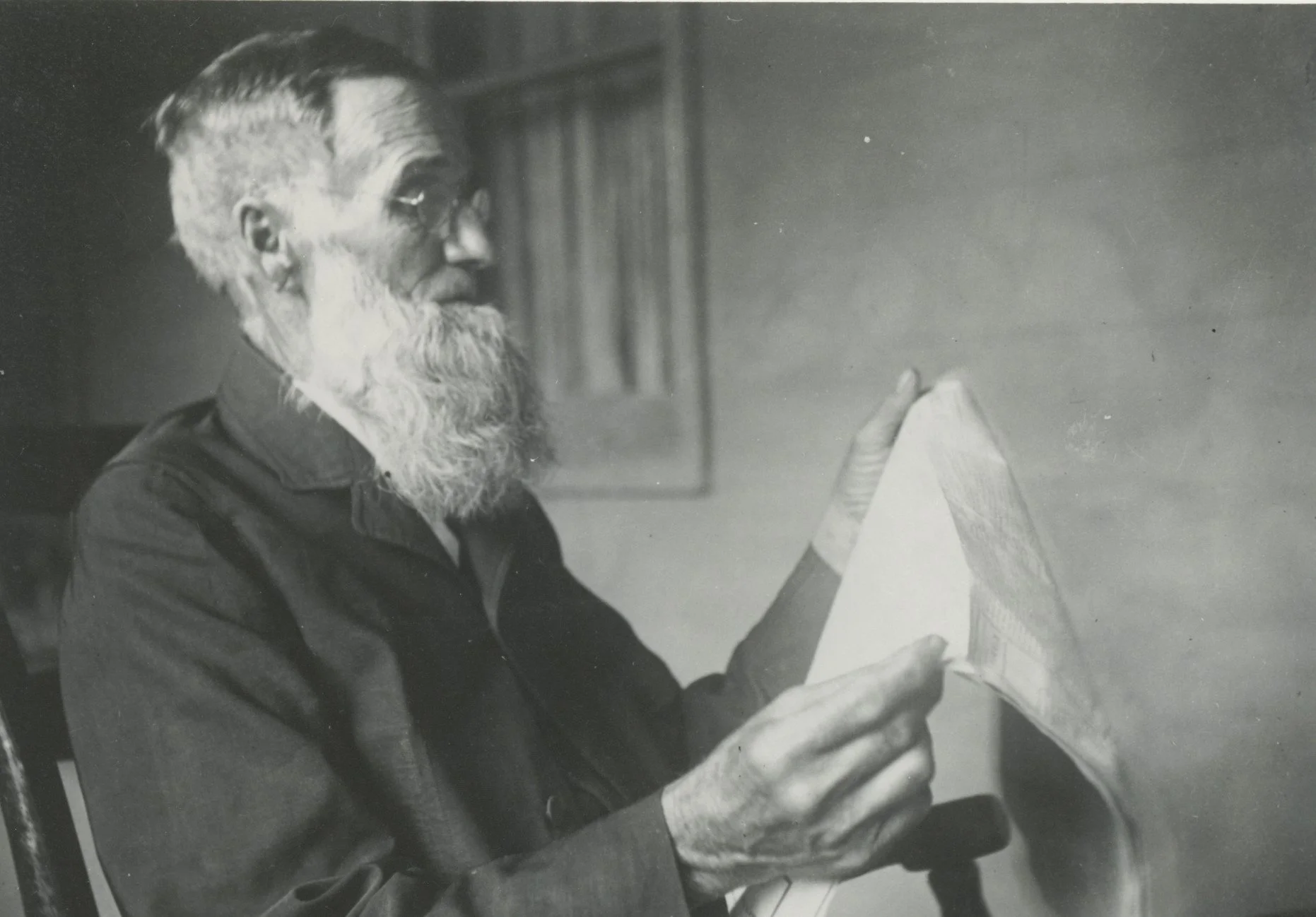

Both Louisa and Nixon Rush had papers from their Friends Meeting recommending them as lay preachers to other Meetings. Nixon wrote in his 1907 journal: “I was successful in finding nice, good young men to work for me. So I could go to different Meetings around… Though I was careful not to impose, I did preach.” ³

Quaker rhythms shaped Rush Hill life. The family went to Meeting for Worship twice a week and the children were pulled from school to attend the mid-week meeting. Myra wrote: “As I always liked school, I resented such an order but there was no getting out of it.” ⁴ She also commented: “Rush Hill was always, in the lifetime of our parents, a great gathering place for the faithful. Especially at Quarterly meeting time, we were swamped with company.” ⁵

Nixon Rush 1907, p 3

Myra Rush Baldwin 1943, p 33

Nixon Rush 1907, p 52

Myra Rush Baldwin 1943, p 22.

Myra Rush Baldwin 1943, p 5

Nixon Rush reading the paper (Rush Family Photographs)

Olive and Myra Rush “dressing up” in their grandmother’s (Elizabeth Bogue Rush Jay) Quaker plain clothing. They did not wear plain clothing in their everyday life (Rush Family Photographs)

Rush Hill in 1886. On roof: Myra, Walter, Clint Winslow, Emma. Below: Charles, Louisa, Olive, Nixon, Calvin (Rush Family Photographs)

Olive Rush in sunbonnet, lower right, watching the threshing, circa 1877 (Rush Family Photographs)

-

1873

Olive is born in Indiana

-

1914

Rush visits SW, has solo show at NM Palace of Governors

-

1920

Rush moves to Santa Fe

-

1932

Rush oversees Santa Fe Indian School mural

-

1957

Rush has 30 paintings in solo show at NM Museum of Art

-

1966

Rush dies in Santa Fe, is buried in Indiana

RUSH’S ART TRAINING AND ADULT LIFE IN THE MIDWEST AND EAST

By age four, Olive Rush knew she wanted to be an artist. At sixteen, she was studying art – for a term at Earlham College in Indiana, then at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington D.C.

Over the next 28 years, Rush supported herself as a commercial illustrator and working artist, while continuing her art training. She studied painting and artistic technical skills at the Corcoran, the New York Art Students League, the Howard Pyle School of Illustration, with Boston teachers, and on European trips with other women artists. She submitted paintings to national and international competitions and became well-known nationally.

During those years, Rush lived and worked in various East Coast and Midwest cities — Washington DC, New York, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, and Wilmington, Delaware — generally in lodgings and studios shared with other women artists. While her parents were alive, she often went back to Rush Hill during the summer months.

In 1914, Rush traveled to the Southwest with her sister and their father Nixon. She learned while traveling that one of her paintings had been accepted for the Spring Paris Salon of 1914, but her letters show she was much more excited about painting Indian children on the road.

On that trip, Rush was offered the first solo show at the Santa Fe Palace of the Governors by a woman artist. It was well reviewed in the Albuquerque Morning Journal: “The pictures are so beautiful, so heart enchanting, that it is a wonder why Miss Rush’s fame as an illustrator has travelled so much further than her genius as a painter of children, Madonnas, Indians, and southwestern landscapes.” ¹

Back in Indiana in 1915, Nixon Rush died. Olive Rush began thinking about a home and studio of her own. Her roots were in the Midwest and East, but New Mexico drew her strongly. She chose Santa Fe, moved there in 1920 when she was 47, and remained there until she died at 93. A year before women were allowed to vote in the US, she was the first single woman artist to arrive in Santa Fe – a pioneer.

Smithsonian Arch of Amer Art, Olive Rush Papers, Series 6, Clippings, Box 5, Folder 6, p 40

Rush Hill Porch c. 1905 to 1910: Louisa, Elizabeth, Olive, Emma, Nixon, Myra (Rush Family Photographs)

At Rush Hill, September 11, 1905. Left to right: Isadore, John, Loreta, Frank, Zola, Calvin, Olive, Elizabeth, Walter, Emma, Myra, Louisa, Nixon (Rush Family Photographs)

Olive Rush painting her father’s portrait at Rush Hill in the summer of 1907 (Rush Family Photographs)

“Louisa Winslow Rush” before 1911 (Collection of Earlham College)

Left to right: Olive Rush, Sarah Katherine Smith, and Ethel Pennewill Brown on the steps of the Howard Pyle studio, c. 1905-1910 (in Smithsonian Arch of Amer Artists, Olive Rush Papers, Series 7, Photographs, Box 6, Folder 7, p 5)

THE SECOND HALF OF RUSH’S LIFE WAS IN SANTA FE

Rush bought her adobe house at 630 Canyon Road from the Rodriguez-Seña family, who had farmed there for over 200 years. She moved the entrance to the side portál (covered patio) and made the front room her studio. She added a guest apartment and turned a garden goat shed into a separate rental, usually rented to artists.

Outside, Rush created a stable for her horse, Pedro, and rode him through town. She established a bountiful garden under the century-old apple trees, with more fruit trees, grapes, shrubs, vegetables, and flowers. The garden’s beauty and produce were shared with friends and neighbors, who also baked bread in the communal garden oven.

Rush became a leader in Santa Fe’s emerging art community – often called the “Dean of Santa Fe women artists” by journalists. She exhibited her work regularly in New Mexico and nationally. She gave dinners, teas and parties in her home and garden. She often hosted or rented to women artists from her prior life back East, including Alice Schille and Laura van Pappelendum, who added their work to the community mix.

She co-founded the Santa Fe Women artists exhibition group. She and Georgia O’Keefe, who had known one another in the Art Student League in New York, shared a cat, Anselmo, in New Mexico. The cat lived with Rush when O’Keefe was back East.

In Santa Fe, Rush developed her specialization in wall painting — frescos and murals. She painted them in many private homes and commercial spaces, and in the 1930’s, in government buildings.

With friends, Rush traveled to nearby pueblos to watch the ceremonial dances and purchase paintings, weavings, and pottery. She painted those scenes and people when permitted. She respected and befriended local indigenous painters, and supported them as a buyer, reviewer, mentor and teacher of mural painting.

Olive Rush Garden Party Invitation (in Smithsonian Arch of Amer Artists, Olive Rush Papers, Series 1, Personal Documents, Box 1, Folder 5, p 16)

“Navajos” 1921. Lou Hoover, wife of President Herbert Hoover, bought this painting.

Olive Rush on horseback in the garden at 690 Canyon Road (Negative 019270, Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

"Indian Children at San Xavier" 1914. (New Mexico Museum of Art, 2931.23)

RUSH’S MURAL WORK WITH SOUTHWEST INDIGENOUS ARTISTS

In 1932, Rush turned down a commission to paint a mural at the Santa Fe Indian School. Instead, she donated her time to help a group of students and staff from various pueblos and tribes design and paint their own mural in the school’s dining room. The resulting work was heralded in the Santa Fe New Mexican. The reporter wrote: “People entering the room last night were subdued. The effect of such striking beauty was not unlike that felt upon looking at the Grand Canyon for the first time. Anything was too much to say.”

During the next year, the indigenous mural painters completed and exhibited over fifty large mural-sized paintings on panels and canvas— in 1932 in Gallup, in two 1933 circulating national exhibits, and at the 1933-34 Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition. The paintings and exhibitions were organized by Rush and promoted by her and her friends, particularly Elizabeth White and John Sloan. A few of those mural paintings, by Awa Tsireh and Oqwa Pi, hang today in the Board Room of the Santa Fe School for Advanced Research.

A 1932 mural by Tonita Peña hangs in the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Rush’s August 1932 diary records how that mural happened: “Tonita Peña, her son & baby were waiting on my doorstep, and I made dinner for them & myself in the portal. Tonita wants to take a panel home with her to paint there… ‘You see I cannot stay away - I leave so many…’ So we must try to arrange it.“ Rush arranged it, and Peña painted Eagle Dance.

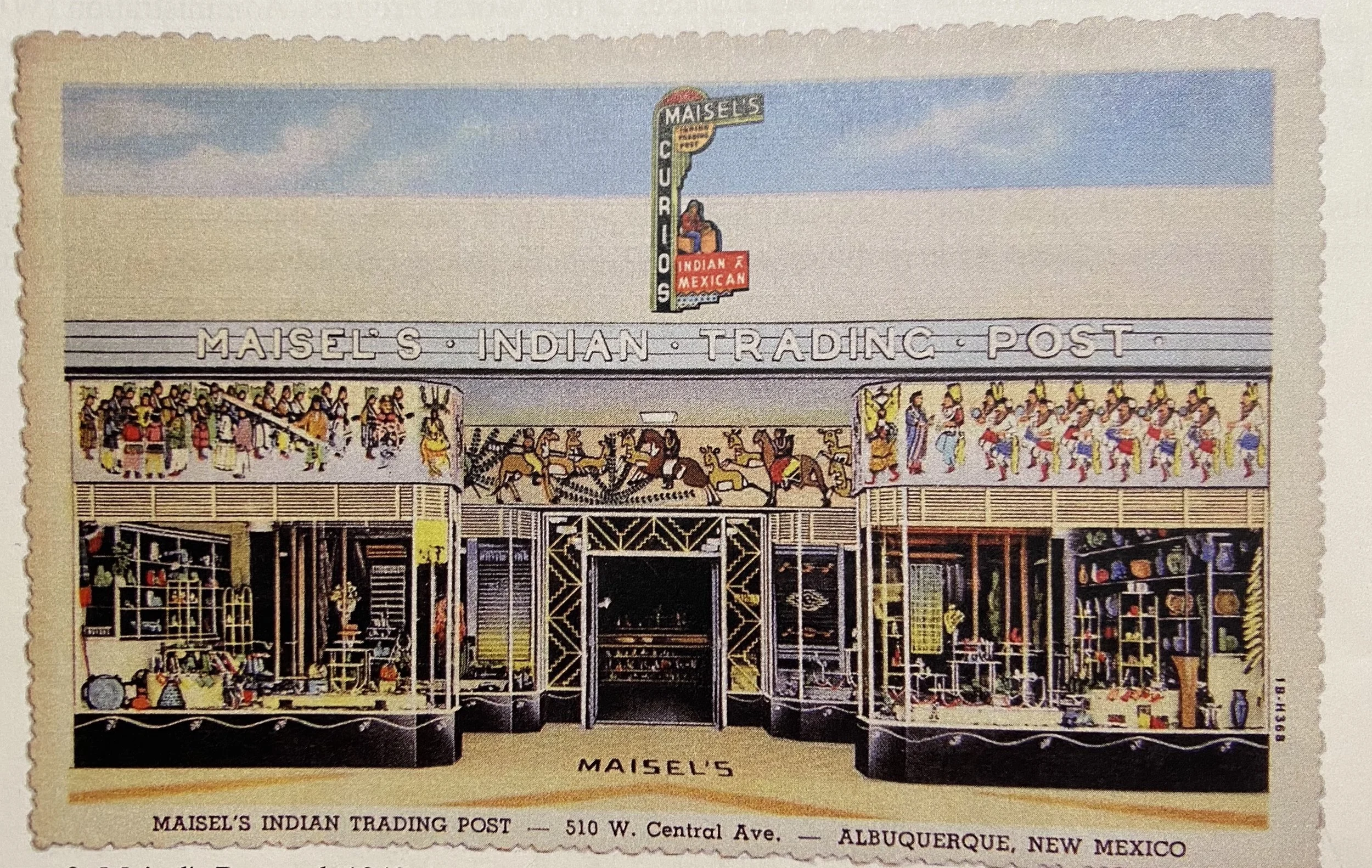

The final mural collaboration between Rush and Southwest indigenous painters was in the entrance and vestibule of Maisel’s Indian Arts and Crafts Store in downtown Albuquerque. These murals still exist. Rush and Awa Tsireh were the established painters in that project. Rush chose the rest from newer students at the Santa Fe Indian School. In his 1918 book, Paul Secord called those painters “an unparalleled grouping of many of the most talented Native American artists of their day.” ¹

In 1988, well-known painter Pablita Velarde from Kha'p'oe Ówîngeh discussed painting those murals fifty years earlier with journalist Bart Ripp. She said of Rush:

“She was quite patient with all of us. She was very feminine, soft-spoken and almost fragile. All of her work had that soft tone with hidden messages. Hers was a great spirit.” ²

Secord 2018, Preface

Bart Ripp 1988, p 2

1939. Collaborative Mural Project at Maisel’s Trading Post in Albuquerque, NM. Painters were Olive Rush, Awa Tsireh, Narcisco Platero Abeyta , Harrison Begay, Pop Chalee, Theodore Suina, Ben Quintana, Joe H Herrara, Popovi Da, Pablita Velarde, Ignatius Palmer and Wilson Dewey. (Collection of Liz Kohlenberg).

1932. The painters, teachers and staff in front of the Santa Fe Indian School dining room murals. Left to right: Unknown, Riley Quoyavama, Ed Lee, Olive Rush, Raymundo Vigil, Chester Faris, Jack Hokeah, unknown, Rush’s assistant Louise Morris, Albert Hardy, unknown, and Richard Martinez. (In Shutes and Mellick 1996, p 57).

“Eagle Dance” Tonita Pena, 1932. (National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma).

RUSH’S QUAKER PRACTICE AS AN ADULT

As an adult, Rush went to Quaker meetings wherever she lived. When she was 34, she wrote in a family round-robin letter: “Last week I was in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. I do wish you had been there. It was beautiful. A real Friends Meeting such as Indiana knows not of because Indiana wants to be like other people… I felt then and feel now that Fairmount Meeting is anything but Friends. But then I say too many things and must learn to keep still.” ¹

When Rush moved to Santa Fe, there was no Quaker Meeting. So, in the 1940’s, Rush helped to start an informal one. She described it lovingly in a letter to her friend Ethel Brown Leach:

“Here we have no meeting house – we only meet at each other’s houses – a very small group—mostly of non-Quakers. We just love our meetings which are spiritual in quality and are like life to us. After the half hour of silence and beautiful spoken thoughts from Alice Howland, or Eleanor Brownell, or Jane Baumann or others, we ‘break the meeting’ by handshake and then something vital and interesting is always to be discussed or read –very informal and delightful … They are the nicest people in town.” ²

This informal group worked hard donating clothing and bedding to war relief during and after WWII. The work began in Rush’s bedroom, but by 1947, it had expanded. “The mayor gave us the largest room in the City Hall – light and warm – and clothes and money keep coming in, and we go three days a week. Working like tigers, mending, sorting, packing and cutting, and making fresh new layettes.”

By 1952, the Santa Fe Monthly Meeting of Friends had grown. Old-time Meeting attenders recall that for some time the group met at the Garcia Street Club. By 1958, the Meeting had been using the Galeria Mexico studio at 551 Canyon Road for both Worship and Business Meetings for several years. The Galleria Mexica was owned by Rush’s friend, the printmaker Dorothy Newkirk Stewart.

Rush described those Monthly Meetings in another letter to Ethel: “We all take our own sandwiches & cookies, finding a pot of coffee always there, and eat on the wide porch at the back. So many young married people belong now that there is always quite a bevy of kiddies who have their one little table after Sunday School.” ³

OR letter to her family, 1907, in Smithsonian, Arch. Amer. Art, Olive Rush Papers, Series 2, Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 14, p 14

OR to Ethel Leach, 1946, Gilmore 2016, p 197

OR to Ethel Leach, 1947, Gilmore 2016, p 201

Peggy Pond Church (Courtesy of the Los Alamos Historical Museum Archives)

Eleanor Brownell (left) and Alice Howland (right) Photo by Laura Gilpin. Gilmore 2016, Page 197

"Portrait of Jane Baumann" n.d. (New Mexico Museum of Art, 4487.23)

Sylvia Loomis (Archives of Historic Santa Fe Foundation)

RUSH BEQUEATHED HER HOME TO HER MEETING

In April 1958, Rush learned from Dorothy Newkirk Stewart's sister, Margretta Dietrich, that the Galeria Mexico had been bequeathed to Maria Chabot and would no longer be available as a Meeting house. ¹ That year, Rush began to consider leaving her property to the Meeting community after her death, if no one in her family needed it.

After several years of discussions and letters about this possible bequest with her family and friends, Rush presented a written offer to the Santa Fe Monthly Meeting (SFMM) Business Meeting on April 27, 1962. It was in the form of an Agreement regarding the disposition and management of her house and land. The purposes in that Agreement were defined as follows:

“The perpetuation of the property as a memorial to the religious, artistic, social, and civic ideals of its owner, Olive Rush.” (Article I-1)

“The continued use of the property for social, rather than commercial purposes.” (Article I-2)

“The protection of the character of the premises, its appearance and use.” (Article 1-2)

“As a resource to the Monthly Meeting as a Meeting House for worship, and other related purposes.” (Article 1-3)

“The uses … may include ... public activities such as meetings, art exhibits, concerts, lectures, hospitality to visiting friends.” (Article II-2.c)

“The premises shall be operated as a memorial to Olive Rush and to her father and mother, Louisa and Nixon Rush, and appropriately identified.” (Article IV-2)

The SFMM Business Meeting Minutes of April 1962 state: “The Meeting accepted and approved this very precious and gracious gift, with gratitude spoken to by members present, and agreed in principle to conditions as presented.” Six weeks later, on June 7, 1962, Olive Rush signed her Will, leaving the house and land to the Meeting and its contents to her family.

During the next four years, as Rush’s health and memory failed, the Meeting community and Rush’s family and friends worked to support and care for her. Eventually she was confined to a hospital and could no longer paint. In August 1966, Olive Rush quietly stopped breathing.

The Santa Fe Monthly Meeting managed 630 Canyon Road from 1966 through 2023. They cared for the buildings and garden, and the property served them well. They held Meetings for Worship each week in Rush’s studio or the garden, had children’s programs in the main bedroom, and turned the dining room into a library.

Hospitality to visiting Friends and family was extended through the guest apartment, and the backyard casita was eventually occupied by a Friend’s Resident caretaker.

The studio was hung with some of Olive’s remaining paintings. Her paint cans and brushes remained in a cupboard, and some of her papers in a wall desk. The house was opened to the public on occasion – at first monthly, and later yearly.

Eventually, the Meeting community outgrew the house. They considered building a somewhat larger Meeting House at the back of the property. But in 2020, they chose instead to purchase a much larger building, at 505 Camino de Los Marquez in Santa Fe.

In 2023, after almost three years of deliberation, the Santa Fe Monthly Meeting sold the Rush house, studio, garden and archive to the non-profit Olive Rush Memorial Studio, Inc. That sale specified that the building would be used in perpetuity as an Olive Rush studio museum and community art center.

Margretta Dietrich to OR, 1958, in Smithsonian Arch Amer Art, Olive Rush Papers, Series 2, Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 57, p 35

Rush fresco on studio fireplace (Photo by Wendy McEahern for Parasol Productions)

Olive’s Studio Set up for Santa Fe Meeting for Worship in 2017 (Photo by Richard Rush)

Entry fresco in Olive Rush garden (Photo by Wendy McEahern for Parasol Productions)